by José Ignacio Cabezón and THL.

En-visioning the Space of SeraSe ra: Non-Tibetan In(ter)ventions

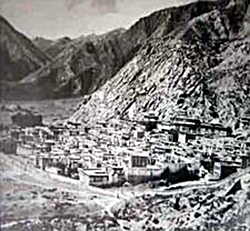

A view of SeraSe ra from the mountain north of the monastery.

When people turn their gaze to the physical space of SeraSe ra, they see different things. Or perhaps it is more accurate to say that what they see they en-vision – they imagine – and represent in different ways. In this introduction to the space of SeraSe ra we will explore some of the ways in which the monastery has been envisioned by different people, non-Tibetans, at different times, using a variety of media: from text to panoramic virtual-reality models. We will be dealing with material from the 19th century up to the present day.

Common sense would seem to dictate that the physical layout of the monastery is a given – that what is there is there ... period. But you will see from what follows that this is not so. That what is there for one group of people is not there for others, even at the same point in time. This will become especially apparent when you compare the views of non-Tibetans (found mostly in this section) with the views of Tibetans (found under Tibetan Perspectives). Euro-American scholars have their own jargon for the fact that space is not a given. They express this by saying that it is a construct: a construction that historically, culturally and linguistically-situated human beings create using their imagination and the tools at their disposal. Tibetan Buddhist thinkers express a similar view when they say that abstract concepts like space1 exist only as human conventions (tanyedutha snyad du), as the “mere imputations of words and conceptual thought” (ming dang tokpé taktsamming dang rtog pas brtags tsam). That space is a construct or a convention does not mean that it lacks power or efficacy, quite the contrary. It is precisely because it is a human construct that it has the capacity to affect human lives.

Constructions, however, do not emerge from nowhere – they are not created ex nihilo. Certain tools are required for constructing a notion of a particular site – sacred or otherwise. Some of the differences in the visions of SeraSe ra you will encounter are the result of the fact that their creators utilize different tools – different media – to depict the space of SeraSe ra. A depiction of the monastery in words is going to be different from one in a painting, which in turn will be different from one in a photograph. But differences in media – differences in the modes of representation – do not explain all of the dissimilarities in the constructions of the space of SeraSe ra. At work here are other factors, like language, history, politics, and the sheer idiosyncrasy of human personalities.

So the medium of construction may not be the only thing that explains the differences in the various visions of SeraSe ra that we will encounter, but it is an important part of understanding these differences. We will structure our discussion according to media, and we begin with the medium of words, or text. Consider these alternative ways of describing the space of SeraSe ra in words (or actually, in words and numbers).

A plaque commemorating the official re-opening of the monastery in the early 1980s.

The great yellow-cap monasteries of Sera and Däpung were visited by some of us ... As the abbot had been notified that we were coming, his staff were ready at the gates to receive us ... Sera, which receives its name from a “hedge of wild roses” which used to enclose it, is situated, like Däpung, at the foot of the mountains, and lies on the northern border of the Lhasa plain some 2 miles from the city… Passing through the gate, we found the monastery was quite a little town of well-built and neatly white-washed stone houses with regular streets and lanes, some of which recalled those of Malta.2

Founded in 1419 by Jam Chen Choje, Disciple of Tsongkhapa, Sera Monastery has an assembly hall, three colleges, and thirty kansas. The monastery, occupying an area of 114964 square metres, is known as one of the three major monasteries of the Gelukpa, or yellow, sect ... [and] was appointed as a State-level Unit of Protection of Historical Relics by the State Council of P.R.C. in 1982.

NW corner = N 29.69920, E 91.13130.

NE corner = N 29.69674, E 91.13527.

SE corner = N 29.69541, E 91.13525.

SW corner = N 29.69827, E 91.13087.

With allowances for errors in the phonetic rendering of Tibetan terms (SeraSe ra has khangtsenkhang tshans, not kansas!), none of these characterizations of the space of SeraSe ra are, strictly speaking, wrong. Indeed, all of them impart important information about the site of the monastery.

All of them, however, also evince the idiosyncratic concerns of their respective authors. Waddell’s 1905 book, from which the above passage was taken, was a travelogue written during the late-Victorian era for a British, upper-class audience. Waddell wishes to make it clear that he actually visited the monastery (that he was actually in the physical space), and that he was received in a manner befitting his social stature. Both of these facts serve to legitimate his work, giving it credence in the eyes of his readers. In a narrative style consistent with the genre of the travelogue, he situates the monastery vis a vis the other sites he visited, and offers comparisons to other places with which his readers may be acquainted (Malta).

The plaque placed at the monastery’s entrance by Chinese officials a decade after its reopening has touristic, bureaucratic and political functions. It provides visitors with certain geo-spatial facts (e.g., the physical size of the monastery), while simultaneously proclaiming its formal, bureaucratic status as an officially designated historical site. In the process, one is meant to glean that SeraSe ra, as a “historical relic,” both belongs to, and is held in high esteem by, the People’s Republic of China.3

Finally, the site of SeraSe ra can be depicted in abstract – here, numerical – terms, which, among other things, provides normally “soft” humanistic researchers with the legitimizing facticity otherwise reserved for the “hard” sciences.

Of course, none of these examples are drawn from the writings of Tibetan. If you are interested in exploring some of the ways that Tibetans themselves have envisioned the site of SeraSe ra, go to Tibetan Perspectives.

The space of SeraSe ra has been variously envisioned not only in and through narratives, plaques and GPS devices, but also pictorially. Consider these examples – three images of SeraSe ra, all created at roughly the same time in history.

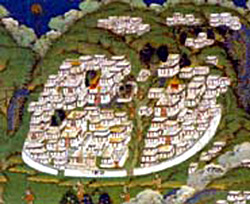

Detail from “A Plan of Lhasa,” published by the Survey of India in 1884. Portion of a photo in Larsen and Sinding-Larsen, The Lhasa Atlas, 8. |  Detail from a painting of LhasaLha sa commissioned by a British official, c.1860. Portion of a photo in Larsen and Sinding-Larsen, The Lhasa Atlas, 20; the original is in the Wise Collection of the British Library. |  Detail of a Tibetan painting in the Musée des arts-asiatiques Guimet, Paris (Jean Schormans). Portion of a photo in Larsen and Sinding-Larsen, The Lhasa Atlas, inside cover. |

The contrast is stark. The first is from a document believed to be the first western-style map of LhasaLha sa, probably created by British colonial officials in India from the oral reports of Indian spies.4 The author is unknown. The second, while commissioned by a British official, was most likely painted by “a monk or a lay priest from the Nyingmapa school from Lahul.” 5 The last is from a traditional Tibetan painting (tangkathang ka) of the important religious sites in LhasaLha sa.

In the first image, SeraSe ra is depicted as an empty rectangle sitting at the foot of stylized mountains. At equidistant points along its southern border, roads intersect its perimeter wall – or is this simply a frame for the words Sára Gomba (Sera Monastery)? The name of the monastery – in some strange fusion of phonetics and transliteration6 – substitutes for the detail that we find in the paintings.7 In the next image, the first of the two paintings, there is a commitment to greater detail on the part of the artist, but the image of SeraSe ra pales by comparison to that used to render, e.g., the PotalaPo ta la in the same painting, where every window is shown. The second of the two paintings, the traditional Tibetan image, renders the monastery in tremendous detail, for more on which see Tibetan Perspectives.

There are of course reasons for these differences in the depiction of SeraSe ra. The three images differ, first of all, because they are different visual genres – maps vs. paintings.8 But they also differ because their creators were differently motivated. They had different goals and reasons for representing SeraSe ra. The British mapmakers who were responsible for the first image were interested in gaining a general sense of the layout of LhasaLha sa for strategic, military purposes. Maps such as this were part of their project of opening up Tibet to trade, a project that eventually led to the military invasion of Tibet, the so-called Younghusband “Expedition” of 1903-04. By depicting SeraSe ra in their map at all, they were acknowledging the existence of a large monastery to the north of the capital. However, it is the roads that appear to be of much greater interest to the British. Rather than simply reflecting a lack of information about the monastery, the fact that the site of the monastery is blank may be an indication that SeraSe ra was not perceived to be a significant factor in military planning, or, less likely.

A detail of “A Sketch Map of Lhasa” by L. Augustine Waddell, first published in 1905. A portion of a photo in Larsen and Sinding-Larsen, The Lhasa Atlas, 24.

When L. Augustine Waddell – part of the Younghusband military expedition – drew his own map half a century later, we find a bit more detail. For example, Waddell seems to be aware of at least one hermitage above SeraSe ra; and from his own visit to the monastery,9 he knew that SeraSe ra was bisected by a central street, a feature that is clearly visible on his map.

A great deal has happened to SeraSe ra since 1903. In the end, neither Tibet nor SeraSe ra were conquered by the British. But today there is a new onslaught of westerners into the monastery – perhaps more benign, perhaps not. Of course, I am referring to tourism.

A tourist map of SeraSe ra found in Mapping the Tibetan World (Reno, NV: Kotan Publishing, 2000, 84), by permission of the publisher.

Produced a century after the British maps, the concern of the tourist map is practical. Despite minor inaccuracies, it gives its intended audience useful information about getting to SeraSe ra from LhasaLha sa (the minibus stop); it shows one where the ticket booth is situated, and it decides for its viewer the most important tourist landmarks (the large temples), even suggesting the route that one should follow (the culturally appropriate, Buddhist, counterclockwise direction). Maps are truly windows into their respective age.

The second of our original images – the Lahuli painting commissioned by a British official – also contributed to the general British project of assessing LhasaLha sa and its environs, and while a military/strategic purpose is almost certain, this does not seem to have been its only – and maybe not even its chief – objective. As the number “74” next to the monastery suggests, the logic of “scientific” inquiry is at work here. It may be the case that the chief purpose of the painting was archival – that it was an attempt to identify and to catalogue the significant monuments of the capital. The detail – one large building surrounded by many smaller ones, all enclosed within a perimeter wall with three front gates – suggests that the artist was minimally familiar with the monastery. The choice to forego greater (or more accurate) detailing of features may be ascribed to a variety of factors, including the mandate given to the artist by the patron. Whatever the reason, SeraSe ra is not a prominent part of this painting, nor is the monastery considered sufficiently important to merit rendering it in a great deal of detail.

By comparison, in the last painting – the traditional tangkathang ka of LhasaLha sa – SeraSe ra is very prominent. Even without allowing for corrections due to depth of field (the fact that images that are father away should – and do in this painting – appear smaller), SeraSe ra is (after the PotalaPo ta la and the JokhangJo khang) the third largest compound in the painting. The level of detail affords the artist the opportunity to portray buildings three-dimensionally. The large temples, debate courtyards, the central “Sand Street,” monks’ living quarters, are all visible, down to a level of doorways and windows. Of course it is impossible to know precisely what the motivations or goals of the artist may have been, but it is likely that they were in part religious – that the painting was an homage to the great religious institutions of a great religious city. Just as artists take great care to correctly render the features and bodily proportions of deities, so too, in this painting, there is a concern for properly rendering the details of the sacred space of SeraSe ra. Hence, one might say that detail is almost a religious imperative, and not a matter of choice.

And now we turn to our last three images of the site of SeraSe ra. The first of these – an old, black and white photograph of SeraSe ra – was taken sometime before 1959.10 The second is a digital photograph of SeraSe ra taken by a member of the SeraSe ra Project research team in 2002. The third is a low-resolution version of a digital image of SeraSe ra taken on February 1, 2002 from the QuickBird satellite hovering above the earth.

SeraSe ra as seen from its from the east. |  SeraSe ra as seen from the mountain directly north of the monastery. |  SeraSe ra as seen from space. Copyright Digital Globe. |

All of the images are attempts at photographically representing the geoarchitectural space of SeraSe ra in its entirety. At least one of the images is in color, which is important because color allows one to distinguish features that would otherwise not stand out.11 There are also differences in the perspective, which shifts from lateral to vertical-lateral to vertical. This move toward greater verticality is the result of a new imperative to create a distinctively modern/scientific image of SeraSe ra: a geo-referenced, digital map. This, in turn, is essential to creating a Geographical Information Systems (GIS) model of a physical site like SeraSe ra. In a model of this kind, features on the map are coded. They are given meaning, if you will (as apartment houses, temples, and so forth).12 You will find a simplified version of such a meaning-laden map on this website. Of course, what is lost in this process of achieving greater verticality with respect to the object being represented is depth-of-field: the image appears flat. There exists, however, software for adding a third-dimension to such models (both in the landscape and in the buildings), and in future iterations of our work we hope to be able to do this.

Photography – of which all three of these images can be considered examples – may seem commonplace to us today, but it has radically changed the study of other cultures in the last century. The British “cultural officer” who accompanied the Younghusband expedition to Tibet in 1903, L. Augustine Waddell, was among the first westerners to take photographs of the sites of LhasaLha sa – one of the first to render sacred space in this new medium. In the Preface to his famous travelogue, Lhasa and Its Mysteries (1905), he revels in the transparency of this new medium, a medium that permits him (and his readers/viewers), he implies, direct access to the truth of things. He believes that his photographs are “direct from Nature,” and that “the colour process” makes his photos “vivid and truthful pictures of the marvellous colouring of the originals.” 13 Waddell is telling us that cameras do not lie, and they don’t tell partial truths. Today, we are a bit less sanguine about the transparency of photography as a medium.14 Like all human products, photographs are seen to be laden with the presuppositions, concerns and purposes of their creators. The same is true of film. And by implication – because it is a medium that combines text, still photography, film, and their byproducts (like interactive virtual-reality models) – the same is true of multimedia digital projects like the present one.

Sera Monastery from the rear.

(View Larger Version – for high-speed connections)

Hint: If either movie does not load properly, try refreshing this page. IE may take longer to load than other browsers.

New technologies usually bring with them new hopes, but they may also bring unwanted consequences. As with Waddell’s expectations regarding photography a century ago, in the present digital age too there is a certain hope that new digital technologies will allow us to achieve a certain truth, and even a completeness of vision, that has heretofore been impossible to achieve. While it is true that digital imaging, and its dissemination through new delivery systems like the WWW, will undoubtedly revolutionize both research and pedagogy, there is also a tendency to overestimate the power of these new technologies.

Let me give you one example of this. Some folks believe (at least implicitly) that a geographical model of a site can, in principal, yield all of the information you could ever want to know about a place – that every bit of data could be referenced to a place on a map. I call this view spatial reductionism. It is a view that privileges space as a variable of analysis: all you need is… well, space. Here, points in space become the fundamental anchors or ground onto which all other information can be unambiguously mapped. There are many reasons for thinking that this view is naïve.15 I will not dwell on these because I am here interested in making another, broader point. Implicit in the spatial reductionistic view is what some contemporary philosophers call the “impulse to totalize.” Totalization is the tendency to think that completeness of vision is achievable, that we can perfectly capture everything that is worth knowing in its totality. Every new form of technology brings with it a new form of this tendency to totalize, and part of the task of digitally-committed scholars in the humanities today (the Tibetan wife of a close colleague calls us lokgyi miglog gyi mi – “electric people”) is to check, or at least to be aware of, this impulse to totalization. Nothing, not even computers, will ever allow us to achieve completeness, a God’s-eye view, and neither will any single variable of analysis – space, time (history) or anything else. And in the process of expanding our ever-partial knowledge, multiple perspectives – using different variables (from different disciplines), without privileging any of them – will always be the way to go.

Having said all this, I admit that the tendency to check this impulse to totalize is easier said than done. I find myself, for example, continuously reveling in the possibilities afforded by new digital technologies, and I confess to being insufficiently committed to realizing the partiality of vision that they afford. (The interactive map of SeraSe ra that you will see on this portion of the SeraSe ra Project website I find particularly astounding and promising, for example.) But being the child of a postmodern age, I realize that in time our day will come; that our work – the work of the “electric people” – will become the fodder for someone else’s critical inquiries; that our own presuppositions will be laid bare, and that new discourses will find nourishment and flourish in the ashes of this one. How or when this will come about is difficult to say, and so while we wait, I invite you to join me in feeling some of this excitement.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- En-visioning the Space of SeraSe ra: Non-Tibetan In(ter)ventions

- Tibetan Conceptions of the Site of SeraSe ra

- Architecture: The Division and Organization of the Space of SeraSe ra

- Guide to the Map

- Notes

- Specify View:

- Specify Format:

|  |  |